HEWITT.MOBI

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

The Times March 04, 2006

Phone revolution makes Africa upwardly mobile

From Xan Rice , in Murang’a

A daily dose of his own home-brew medicine kept him young. But it took a battered old mobile phone to set Kabiru Gakungi’s business free.

“I can be anywhere, any time and people can still find me to order my products,” the sprightly 77-year-old herbalist said as he prepared to leave his home, which has no electricity or running water, to meet friends in Murang’a, north of Nairobi.

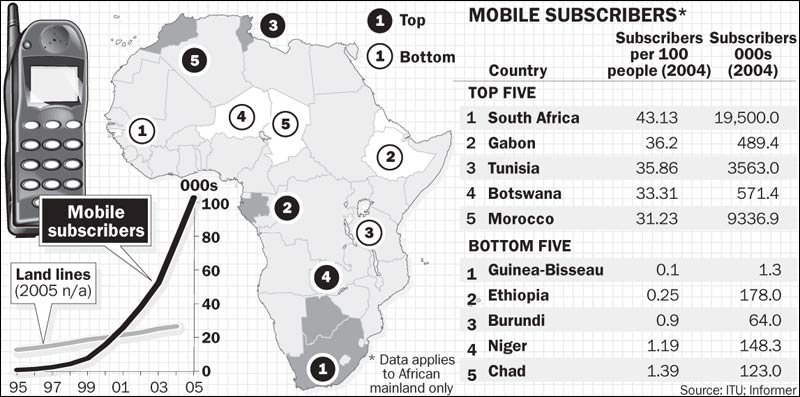

“This phone has become my office,” he added, smiling as he held up a Nokia registering a full bar of signal. Mr Gakungi and others like him are helping to drive a wireless revolution that has made Africa the world’s fastest-growing mobile phone market. At the start of 2000, there were eight million subscribers in Africa. According to a report by Informa, a telecoms analyst, there are now more than 100 million mobiles in use on the continent — one for every nine Africans.

Phone masts tower above cities such as Cape Town and Cairo, war–torn capitals such as Mogadishu and Monrovia, rural villages never touched by telephone lines and even remote refugee camps such as Kakuma in northern Kenya, where text messages and irritating ringtones are now as much a part of life as food handouts.

This remarkable growth — the African market is expanding nearly twice as fast as Asia’s — has confounded analysts and even service operators. As recently as 2003, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) forecast that there would be only 67 million users by the end of 2005.

“Many of us underestimated the strength of the informal sector in Africa,” said Michael Joseph, chief executive officer of Safaricom, Kenya’s biggest operator, with four million customers. “And the huge need and desire for people to communicate.”

Before mobile phones, vast swaths of Africa were communication voids. There are just three landlines per hundred Africans and most are expensive and unreliable. By contrast, Europe has 40 fixed phones per 100 people.

Never having had access to a fixed line, Mr Gakungi made the leap from letter-writing to wireless communications. He buys about 2,000 shillings (£16) of airtime a month but considers it money well spent. “You have to spend to earn,” he said.

South Africa, with its booming economy, is the continent’s biggest mobile phone market, with nearly 25 million subscribers, then come Nigeria, Egypt and Morocco. But it is in less-developed countries that the statistics are most startling. The Democratic Republic of Congo, population 60 million, has 10,000 fixed telephones but more than a million mobile phone subscribers. In Chad, the fifth-least developed country, mobile phone usage jumped from 10,000 to 200,000 in three years.

A lack of electricity has not proved a hindrance: roadside vendors charge mobile phones with car batteries. As the signal coverage expands, cheaper phones and calls fuel growth.

Last month Safaricom started selling what is believed to be the cheapest mobile phone. Designed by Motorola for the developing world, it costs £20, with free connection. The cheapest airtime voucher is about 40p.

In Kenya it is possible to buy talk-time and send it to the phone of a relative, who then cashes it in at local stores. Where few have access to bank accounts, airtime is currency.

Charlie

hewitt.mobi Posted at 7:18 pm |

0 comments

0 Comments: